Interview: Emma Wesley

Interview by Claudia Massie

Emma Wesley is one of Britain’s foremost young portrait painters. She has won numerous awards for her work and is a member of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters. Her commissions include Oxbridge professors, Johnson Beharry VC and the Lord Chancellor, Jack Straw. Claudia Massie tracks her down for an exclusive interview for NLP.

NLP: What made you choose to read English Literature at Selwyn College, Cambridge rather than train at art school?

EW: I had always drawn and painted and always read. When I left school, I considered applying to art school but couldn’t find one where I could just get on with what interested me – that is, painting people. Instead, I read English and continued to paint in my spare time.

Do you have any regrets about missing out on an art school education, or do you feel that doing so has allowed you to follow your own path with a resolution and liberty that might have been weakened by exposure to the current mores of the art school establishment?

As a self-taught artist, I have been free to develop my own rather idiosyncratic style and technique, for better or worse! There are certain art schools which leave their mark very clearly on the work of their pupils, although I think that all the most interesting artists are essentially self-taught, whether they’ve been to art school or not. I do sometimes regret the time to paint and develop that three years at art school would have given me – I often feel like I’m trying to catch up – but artists continue to learn throughout their lives.

Why did you choose to study art conservation at the Courtauld Institute and to what extent does the knowledge gained there influence your working practice?

By the end of my first degree, I was spending more time on my painting and less on my writing, and knew I wanted to pursue a practical, artistic career. Although I’d sold a few paintings, at that time I wasn’t sure if I could make a living as a portrait painter and thought picture restoration might be the answer. What I learnt at the Courtauld was a different kind of art history – a history of materials and techniques, the day-to-day concerns of artists – which has profoundly influenced my own painting.

Why paint portraits? What, do you feel, can a painted portrait offer that a photograph cannot?

A photograph captures a moment, a painted portrait is more of a meditation upon the subject.

Your work is reminiscent of Freud in the early 1950s, is he an influence and if not, who is? Which artists interest you, in portraiture and beyond?

I like Freud’s early work, but my main influences are actually early Flemish painters such as Jan Van Eyck and Roger Van der Weyden. Although I tend to work on a much larger scale, and in acrylic rather than oil, I work in a similar method, building on a detailed underdrawing with thin layers and glazes of paint. Other portrait painters I admire are Hans Holbein, Hans Eworth and Anthonis Mor, although some of my favourite portraits are 16th century English School ‘Unknown man by an unknown artist.’ I also feel a certain affinity with artists from early twentieth century – such as Stanley Spencer and Eric Kennington, who painted modern life as they saw it, but were also looking back to much older artistic precendents.

You paint in predominantly acrylic. What is it about this medium that appeals to you? Do you work in other media at all?

I find acrylic to be a most versatile medium – you can use it like watercolour, tempera or oil. I like building up my paintings in thin layers and glazes and, because of its quick drying time, acrylic allows me to do this in a way oil wouldn’t. I have worked in oil and pastel in the past, but am currently only working in pencil and acrylic.

Which colours form the basis of your palette, or is it entirely dependent on the subject?

Each painting has its own colour scheme – usually based around two or three main colours – which is entirely dependent on the subject. I”m currently working up a composition which will be predominantly black, white and red, although this opposition of colours will appear subtler in the execution than it sounds in the planning. Looking round my studio, I actually seem to be using a lot of blues and greys at the moment. When painting skin, I’m always using complementary colours – such as reds and greens – over each other or against each other, as it’s the only way to get that subtlety of tone.

What kind of preparation do you do prior to undertaking a portrait in terms of researching the background, character and interests of the subject? What is it in particular that you look for to represent individuality and how do you express this in the painting?

I like painting people in their workplaces, surrounded by the tools of their trade, or by objects which symbolise the work they do. Inspired by Dutch paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries, I have painted an antique dealer in his shop and a butcher in his cold store. The props, or symbols, in these cases, are obvious. Some portraits, of academics, for example, require more background reading and, in the course of my painting, I have learnt about subjects as diverse as neuroscience, early music and ancient philosophy. The challenge then is often to find a visual expression, or symbol, for the intellectual. In my portrait of Professors Chris and Uta Frith, both neuroscientists, the whole composition is based around metaphors for the brain, taken from their own writings. Thus, objects in their living room – a chest of drawers, a pack of cards, their collection of abacuses – become symbolic of their work.

The position of a person in a portrait is often significant. Is this something you have in mind in advance or is finding the correct position a collaborative process with the subject and dependent on their comfort and ability to hold a pose? What, if anything, do you do to relax the sitter?

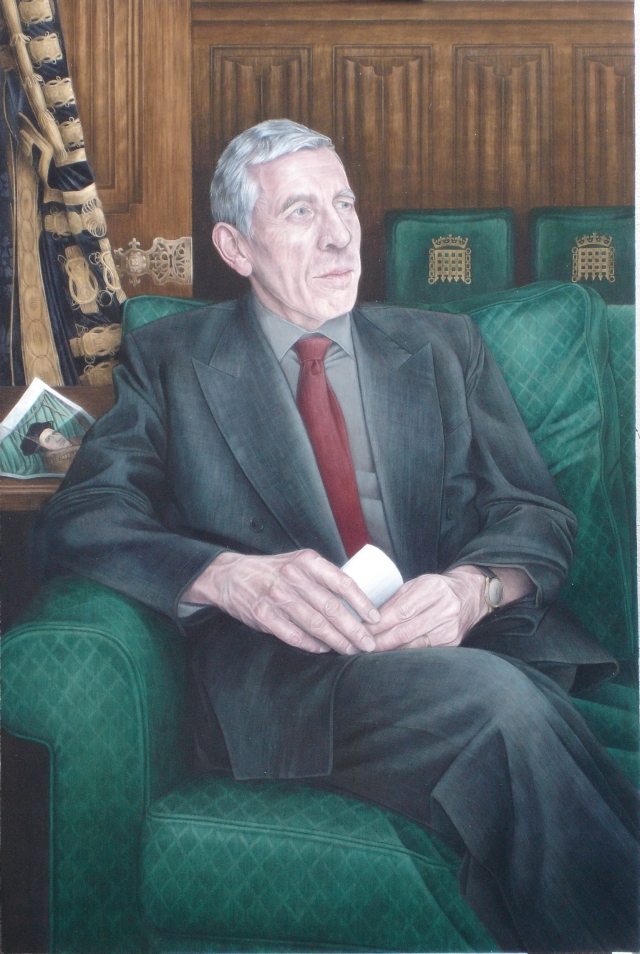

Often, it’s a case of finding how the sitter is most comfortable – and how they are most themselves. It may take a while to find this. Occasionally, I do have an idea for a pose before meeting the sitter – often a reference to an earlier portrait that I’m keen for the sitter to emulate (as in the portrait of Jack Straw, which echoes Holbein’s portrait of Sir Thomas More).

How many sittings do you usually require? Do you work exclusively from life, or do you use sketches or photographs to help you work back in the studio?

As many as possible – but usually 3 or 4 sessions at the beginning, during which I make an initial sketch. I then work up the composition from this sketch, photographs and other still-life elements back in the studio. I then need to sitter for three or four painting sittings to complete face and hands. I also find photographs useful reference throughout the whole process, allowing me to work on a portrait between sittings.

You painted a portrait (above) of Lance Corporal J Beharry VC which is now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. How did this commission come about?

The painting was commissioned directly by the National Portrait Gallery.

In light of your experience working with Beharry, did you feel conflicted in any way when painting Jack Straw, given that it could be argued Straw was at least in part complicit in the extreme trauma suffered by Beharry? Is it necessary to have any kind of personal relationship with your subject?

The painter cannot be indifferent to their subject and should not be indifferent to world affairs. One of the difficulties of the Beharry portrait was to paint a war hero, without appearing to celebrate, or even condone, a war in which I did not believe. I thus painted Johnson as a young man who had acted very bravely, but had also been very badly injured in action. As it turned out during sittings, Johnson himself was far from pro-war and his direct gaze in the portrait was intended to ask the many questions about the war which he had been denied the opportunity of putting to the government.

Jack Straw is also a portrait of a man doing his job. Here, however, the subject looks off into the middle distance and the reference to Holbein’s portrait of Thomas More raises questions about the role of Lord Chancellor. I have long been fascinated by the folded piece of paper that More holds in the portrait and, when I was commissioned to paint the present Lord Chancellor, realised it was the perfect symbol of the power such men hold over pieces of paper which translates, of course, into direct power over our lives. This power is represented in the portrait by the lock and the portcullises on the chairbacks

In your Jack Straw portrait, you included a copy of Holbein’s 1527 portrait of fellow Lord Chancellor, Thomas More. What was Straw’s reaction to being implicitly compared to a figure described by writer and critic James Wood as ‘unscrupulous, greasy, quibblingly legalistic…when he was not lying, he was dissembling’?

It was perhaps not the comparison he would have chosen himself!

Do you find it harder to paint strangers or those already known to you?

Strangers, initially, but drawing someone is one of the best ways to get to know them.

Are there any figures you would particularly like to paint? What plans do you have for the future?

A long-term project of mine is to paint a series of large-scale portraits of market traders – based on the Dutch paintings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. When this will happen, however, is another matter…

Emma Wesley (b. 1979) is a portrait painter who lives and works in London.

She has exhibited widely and shows her paintings regularly with the Royal Society of Portrait Painters, to which she was elected a member in 2007. She has work in many private and public collections, including the National Portrait Gallery, London.

She undertakes commissions from small head studies to large group portraits, and is particularly interested in painting people in their working environment, surrounded by the tools of their trade.

Great interview. It really is a good idea to get an artist to interview another as there seems to be a greater deal of empathy between the two. However, I particularly liked the way you both skillfully danced around the controversial subject of Straw vs Beharry. A revealing and educational interview. Emma, your painting and indeed your theory continue to beguile and enchant.