Steven Severin on Jean Cocteau

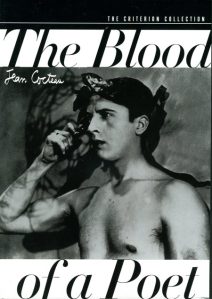

“A poem is a coat of arms. It must be taken apart. Only blood and tears, traded for its axes, its muzzles, its unicorns, its torches, its blackbirds, its benches of stars, its fields of blue! Free to choose the faces, the forms, the gestures, the tones, the deeds, the places that he likes, he creates with them a realistic documentary of unreal events. The musician will emphasise the noises and the silences.” (Cocteau’s manifesto from the beginning of ‘Blood of a Poet’, 1930)

I The poet’s scars

New Linear Perspectives met with Steven Severin, musician, composer, and co-founder of Siouxsie & the Banshees, in the small Slovakian city of Bratislava, a bright, cold nexus of Central European culture where the local spirit hruska is a glassy-eyed institution. Severin was performing the film soundtrack that he has composed for Jean Cocteau’s first film, ‘Blood of a Poet (1930) at the A4 Zero Space on Námestie SNP in the centre of Bratislava, one stop on a Central European tour that took in Kosice, Brno, Prague and more.

NLP wanted to know about Severin’s stripped down approach to Cocteau’s film, suggesting the original soundtrack may have been a major obstacle, or at least a consideration, in Severin’s treatment of the film. But Severin underlines “it’s the film I’m interested in… I don’t want to diss the soundtrack but it sounded very of its time and I think there was a style of surrealist music that went into these films that was quite whimsical”. Severin’s atmospheric electronica lends itself well to a treatment of images, and the whimsy he hears in the orchestral soundtrack that accompanies the strident voiceover in the original film is replaced – by a minimalist wave of sound, containing slowly expressive repeated phrases and fragmented voice-sounds. ‘Blood of a Poet’ is many times refracted, and Severin distorts and dissembles. Arguably, blanking the soundtrack and narration to entirely replace it is a bold move, but this reimagining is surely done in the bombastic style of its creator, for all Severin’s understated modus operandi. The A4 space on Námestie SNP is packed and the show starts late, latecomers still filing in after the lights go down.*

II Do Walls Have Ears?

After the show, NLP seeks Severin out; he is outside the concert hall posing for photographs with Slovak fans. We smoke in the cold Bratislavan air; he is unassuming and soft-spoken, accompanied by an old friend who he has know since before Severin co-founded the Banshees with Siouxsie Sioux. His Czech assistant Martin, on the road with him for the Central European leg of the tour, has clearly formed a comfortable relationship with Severin and the atmosphere is easy – Severin is easy in his own skin. However, Cocteau’s surrealist influence seemed to ooze out of the unfamiliar Bratislava streets that clanged with trams. It was not exotic, but small elements skewed the sense of the real. NLP ordered drinks, they came back tiny but incredibly strong. NLP ordered food – Chicken ‘Edith Piaf’. NLP sat beside punk hero Severin and discussed his take on ‘Blood of a Poet’ as if it was the most natural thing in the world. Cocteau listened from the walls with unrestrained glee.

III The Hotel of Dramatic Lunacies

NLP: What drew you towards Cocteau’s film in the first place?

SS: Although I’d always been a fan of Cocteau’s work in general, I hadn’t seen Blood of a Poet for many, many years. The first film I did in this series was Seashell & the Clergymen; that (choice) was only logistical, as that movie was only 28-30 minutes long. I had to fill out the performance with some short movies that I’d found, and I just wanted to bump up the timing – I saw that Blood of a Poet came in at 55 minutes and I thought that was the next step for me out of a shortlist of a few films… I didn’t want to make a full 90 minutes where you might be demanding a bit too much of the people to sit there and watch it…

I think I probably subconsciously picked up on the idea that there is a single male protagonist in each film and they both go into their own dream-like worlds that they have no control over whatsoever, I kind of liked that it linked the two, and the third and final one I’m going to do is Karl Dreyer’s Vampire (he did Passion of Joan of Arc) – again a single male… everybody does ‘Nosferatu’ and I didn’t want to do that. It’s about time I showed the ‘Twilight’ generation what it’s all about!

NLP: How did Georges Auric’s original score affect you?

SS: Obviously I heard it. I never take any notice, I simply…as soon as I start working I rip the music off the film and look at the images. Very similar to how I would work on a commerical project, where there’s no music given to me or there’s guide music to show me where to put things… Dreams that money can buy (ed: 1947 surrealist film by Dadaist Hans Richter) and Ballet Mechanique (1924 project by filmmaker Fernand Léger & composer George Antheil) had this music that I love but I take it out and look at it anew…

NLP: The film is dedicated to various painters – Pisanello, Paolo Ucello, Piero della Francesca, Andrea del Castagno (“painters of coats of arms and enigmas”) – which painters influence your work if any? – how would you equate the art of sound creation and soundscaping with that of painting and the visual arts?

SS: I would say a very visual artist like Francis Bacon. I can see the sound of that – and then other artists for the conceptual stuff they bring to their work – but Bacon especially.

NLP: In his last film, Orphée, Cocteau suggests that “an artist always paints his own portrait”. How much of Steven Severin is now superimposed on Cocteau’s original vision?

SS: Well, in one sense all of me because everything I do is first and foremost to please myself and I make sure I’m going where I want to go, but I like working with film because it’s very structured – it’s very disciplined, and I like something or someone else containing me… you have to be subservient to the image…

NLP: then perhaps ego doesn’t become too involved in that sense?

SS:…and that’s why I’ve become involved with electronic music as it’s interesting to play with music that doesn’t have a core ego or special focus. When you have a singer and a song it’s like a pyramid, obviously you can do lots of things to change the levels of things… but there is always an axis by having a voice in there – because it’s natural for us to want to hear what they are imparting to us, so you extract that and you can play with pushing the audience to focus on something else, while a lot of things are bubbling underneath somewhere else, so you can bring layers in and out that’s what I enjoy

NLP: maybe it’s more subtle?

It’s probably too subtle, but that’s how I like it!

IV The Desecration of the Host

IV The Desecration of the Host

Jean Cocteau’s 1930 film ‘Blood of a Poet’ is a seminal work that puts the artist and his metier through a proto-surrealist series of netherworlds. Steven Severin is the co-founder of 1970s art-punk band Siouxsie & the Banshees and a prolific film-scorer and composer. The conversation between these two particular artists creates a fascinating postmodern take on ‘Blood of a Poet’ and happily distorts the temporal frame imposed on Cocteau’s early twentieth century cinematic vision.

This duality also distances them: Cocteau and Severin occupy different ends of a spectrum, artistic as well as temporal. Cocteau was a bombastic film-maker just starting out on a long career, whereas Severin is a long-serving punk icon who has stepped away from his band to explore understated avant-garde territory. However, it is Severin’s subtlety of hindsight that allows audiences a reflective, contemplative space to re-imagine Cocteau’s film for a new era. Cocteau’s 1930 film is a wry treaty for artists to reflect upon themselves surreally, but in Bratislava Severin creates a further dimension for Cocteau’s poet to explore. Severin does not merely accompany the film, but splices a further self from Cocteau’s poet and re-imagines him as a dark-suited Mac-boffin. He expands Cocteau’s surreal journey with a mesmeric electronic soundscape quite different from Georges Auric’s original soundtrack but equally, if not more, affecting. The performance underlines an epic link between the two – an invisible vein throbbing with the ‘blood of a poet’ that Cocteau detailed in his film. Severin and Cocteau’s ostensible disparity offers another more prosaic connection – both are enfants terribles of their particular genre and push boundaries outwith of the western European/ US canon, a canon that can be dangerously reductive and ignorant of the instersitial undercurrents of transnational expression.

Severin seems to argue that his postmodern glimpse of Cocteau’s vision strips the ego from it, or certainly subsumes the ego within an avant-garde soundscape. The idea of an artist without ego is something Cocteau would not, perhaps, understand – the man who signed his own screen mid-film and performed a “a strip-tease show where I take off my body” (Cocteau, 1957). The idea that the ‘focus’ for Severin is not a singer and, latterly, a song, suggests that his past in Siouxsie & the Banshees had to come to a natural end. There is only so much you can extract from a musical ego before it becomes redundant or repetitive. His successful journey beyond the rock artist he started out as, and the transformation of that self into a quietly travelling interpreter of important, strange past cinematic voices suggests a real artist, a shape-changer who is aware of the travails of modernity and is capable of communicating them; Severin’s voice is necessarily ambient, a mute clutter of electronic symbols and ethereal motifs, and his desire to perform that voice across the world and his understated love of his craft seems to NLP to be a meritorious ideal.

* For a full treatment of Cocteau’s film, check out NLP film critic Katy Karpfinger’s essay that accompanies this interview.

Thank-you to: A4 Zero Space – Asociácia zdruzení pre súcasnú kultúru/ Námestie SNP 12, Bratislava

Antik Café, Rybárska Brána, Bratislava

Martin, Cliff, Fleur MacIntosh photographer (of Godiva Boutique)

Steven Severin founded the Banshees in 1976 with Siouxsie Sioux and was a key member of the infamous ‘Bromley Contingent’ that helped redefine fashion and music in 70s England. Since the band’s split in the 90s Severin has concentrated on solo projects such as re-defining film scores for a new generation. His first collection of erotic prose/poetry The Twelve Revelations was published in 2000. He has also written original film scores (such as 2003’s supernatural thriller London Voodoo) and will soon be performing ‘Blood of a Poet’ to the US, Mexico and Australia.

You can catch Severin in the UK at the end of March – check his website for details.