Alastair Cook: The In-Between

In the problematic space inhabited by the spectator of a photograph (us, in this case), we experience a strange dislocation from the object itself; a sense, according to art critic Michael Fried, of ‘estrangement’. Fried goes on to suggest that the spectator is beset by the theatricality, or artificiality, of an image through an emphasis on the ‘deliberate construction and labour that are involved in the making of photographs’, whilst acknowledging that the photograph itself opens up into another realm or space. There is a sense of being in-between, a dizzying sensation – when we confront a photograph from our place in time.

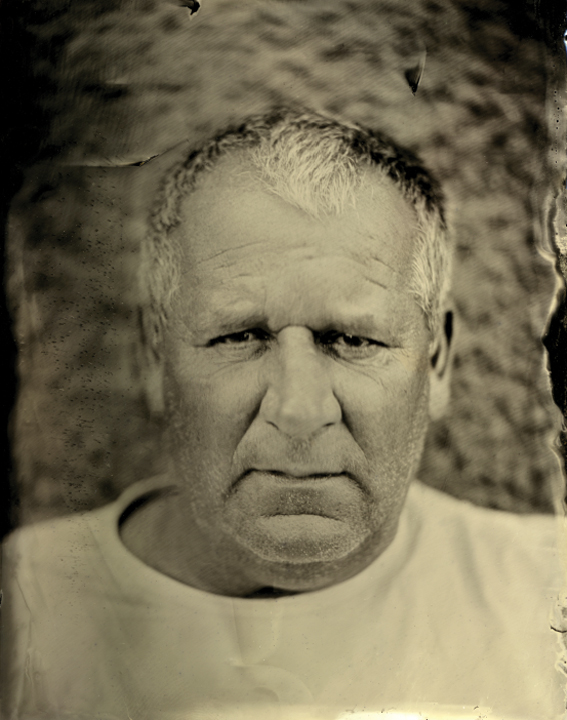

This dislocated feeling of overlap insinuates itself into the wet-plate collodion portraits of artist Alastair Cook. How can we approach Cook’s silvered, ingrained images? The work of photographer Thomas Ruff (b. 1958) – his passport-style portraits of people’s faces from the 1980s that foreground a world of surveillance and identity, for example – has been described as defying meaning through its ‘muteness’ or ‘blankness’. This blankness is also the engine that triggers meaning; it is the feeling of being in-between that nears us – and distances us – from the photograph. It is this paradox of inherent muteness in photography that seems to best describe the weathered and brooding portraits produced by Cook for his recent residency at McArthur’s Store in Dunbar – exhibiting from 30th November until 21st February. Cook’s photos are marked and mottled, the result of working in the dusty atmosphere of McArthur’s Store, a building from 1658. There are other traces, less tangible, however, that may resonate in the images.

If a modern experience of photography does induce, then, this strange sensation – what of an artist who seems to trap time by reverting to techniques that time has made obsolete? Wet-plate collodion is a nineteenth-century process that displaced the daguerreotype.

There are various artists working in the medium in Scotland – Katie Cooke being the most well-established, with Carl Radford, the most established teacher of the process, each having been taught by one of the greats of the technology, Kerik Kouklis. Other established artists – Joni Sternbach, John Brewer and Quinn Jacobson – are also enthralled by this medium. An internet search throws up a plethora of images in danger of falling into stereotype – scratched- and damaged-looking images, a frontier sense of decay and falling away, strangely holographic skin, sharp freckles like animal prints, voodoo eyes. What can Cook add to Walter Benjamin’s ‘mechanical’ reproduction of the past (that does not, perhaps, look like the future) – whose elusive blankness, in fact, could be exploded by its ubiquity?

To confront the problematic nature of Cook’s foray into wet-plate collodion portraits, I had to consider a few different variables: Cook’s respect for the local and his desire to document the working people of Dunbar; the validity of the eerie beauty of wet-plate collodion as an artform; and finally, the danger of any analysis flattening the spectral muteness of Cook’s images. According to one critic, ‘the critical capacity of photography… comes… out of affirmation of what we might hope to hide, deny or reject’. The variables that I felt it sensible to consider met a veritable matrix of hiddenness, denial and rejection that characterises the space of the in-between, the meeting of the spectator and subject.

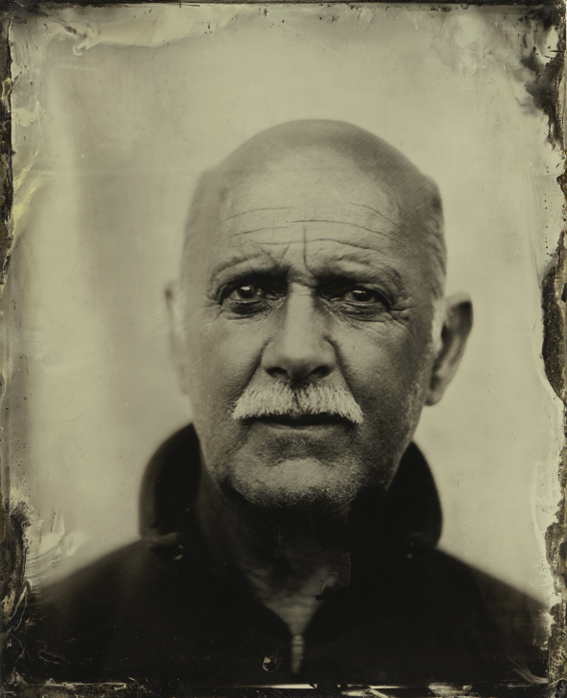

In his portrait ‘Eddie Macfarlane, Dunbar’ (2012) [see above], Cook captures a fisherman’s iconic gaze as he confronts the eye of the camera. Cook’s subject looks firmly – even menacingly – out of dark, viscous depths that do not reveal the entirety of the face, but do reveal rugged contours – deeply ingrained wrinkles made by weather. Momentarily, the head seems to float, as if disembodied. The subject is at once Cook’s ‘fisherman of Dunbar’, a man engraved by wind and seasalt and scratched with that marine spectre into the glass. The subject is also a ghost within the camera lens; his head is not fixed within the image and seems to be falling, dragged down by the weight of the lines on his face – which could be an effect of the wet-plate collodion process, of nature, or of something else entirely more spectral; his eyes look directly – but blankly – into an unseen hell. There is a palimpsestuous effect that the process enjoys that suggests a many-layered function to time, present within the glass. Cook takes on the mantle of both a recorder of culture and a devilish prison-guard, fixing wounded monsters within his camera. Strangely, the subject also retains a starting similarity to the theatre actor/director Steven Berkoff. Within this roiling confusion of temporal layers, Cook has captured the non-subject – he has captured somebody else, somebody who wasn’t there. Taken in terms of the ‘estrangement’ of the object, a space of absence is evoked (Badiou’s ‘ab-sense’) where identity escapes the spectator. What the photograph hides, rejects or denies is absolutely your guess – your chance to confront the blankness of representation – but there is an ambiguous liminality caught within the image that is both fascinating and uncomfortable.

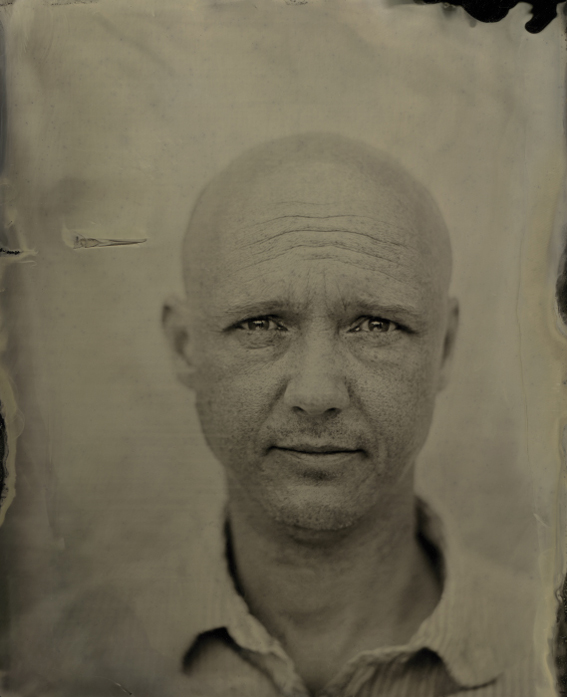

In ‘Brittonie Fletcher, Boston’ (2012), Cook has achieved a clever effect. The subject, on first glance, has a large, frizzy head of hair. On further inspection, the ‘hair’ has melted and joined with the grey-silver background of the image to suggest a freckled head immerging from a smoking, confusing background. Like in ‘Eddie’, the background seems as depthless as it is deep. This is where it is possible to confront Cook’s use of an antique process in the present. The process, used in the twenty-first century, is loaded with an oblique morass of time that sits invisibly behind the glass and, via the wet-plate process, is even seen to seep out of it. Just as it seems ‘old’, a frontier image blackened by time passing, so does it also seem to have a grip on time, or sit outside time altogether. The spectator is forced to (at least) confront their sense of time when gazing on these images. Back to the head: the ‘Brittonie’ head emerges bald and naked out of primordial swathes of grey mist. Her face is marked with tribal patterns – nature’s tattoos. The effect is weirdly ancient. However, our gaze is drawn to her necklace (a kind of hollow sun) and modern clothes, which flattens the effect – until we notice that the clothes are melting back into time – possibly into the past. It is not clear. Time is multiplied, certainly, and it seems as if the present is subsumed in the past: ‘I am includes all that has made me so… the exposure time is the lifetime’ (John Berger). When discussing another photographer, Paul Strand (whose famous portraits are arguably contained in Cook’s work), Berger tells us that ‘such evidence of a life is social comment… (but) such evidence serves to suggest visually the totality of another lived life, from within which we ourselves are no more than a sight’. Cook’s ‘Brittonie’ peers at us from her misty vantage point – we are the hidden, the denied, the rejected.

Cook calls his work ‘quietly ad-hoc’. ‘What more could an artist want’, he asks, ‘than to be in the thick of it?’ He means around and amongst the subjects of his portraits; but his involvement with the process, whilst being physical (I refer to processing the plates) is a lot more ambiguous than just the involvement of an artist in the documentation of a locality. The tears and rips in the fabric of the plates that we are confronted with in this work are Barthes ‘subliminal text’, a message encoded in the blankness of representation. The message, confused by ambiguous time, is sometimes monstrous, sometimes elegiac, and always uncertain. Barthes spoke of the photograph’s ‘intimate connection’ with the object – he was suggesting that a photograph could, after all, ‘attest to the reality of the thing’ – Cook’s real fishermen and ‘their boys’ with real lived lives. But this reality we half-sense in Cook’s images is ‘a reality in a past state, an ectoplasm, a reality one can no longer touch’ – a phantom of Berkoff. At the same time, as Berger would have it, there is life (or ectoplasm) running through the project, however hard that is to conjure. Cook’s images, according to Berger, ‘reveal to us the stream of culture or a history which is flowing through that particular subject like blood’. Indeed, the streaks and smears in the glass – part of the process, for sure – are also temporal traces and traumatic evidence of blood. Trauma – a process often allied with gaps and wounds in the fabric of time – would perhaps return us to the rushing sensation that whistles and roars at us in these images – like waves crashing down.

Alastair Cook’s award winning film and photography is driven by his knowledge, skill and experience as an architect: this mercurial work is rooted in place and the intrinsic connections between people, land and the sea. Alastair trained at the Glasgow School of Art then fled the country, returning after a dutiful spell in London and a more relaxed time in Amsterdam; he now lives and works in Edinburgh with his young family.