Interview: Andrew Mackenzie

Interview by Claudia Massie

Andrew Mackenzie is one of Scotland’s most interesting artists, a complex and meticulous painter whose work inhabits the unexplored edges of landscape. To coincide with his current exhibition at Sarah Myerscough Fine Art in London, Andrew speaks exclusively to NLP about his work and vision…

NLP: Your paintings are landscapes but they focus very precisely on the line between the natural and manmade environment. What is about this facet of the landscape that appeals to you?

AM: I grew up in a small village in NE Scotland. I used to play a lot in the nearby wood, called simply “the hill”, which had at the top an obsolete concrete lookout-tower. I had no idea then what this structure was for, or why it was there, but it stayed in my mind for years after moving to Edinburgh to study. I re-visited this site many times after leaving Art College (in 1993), and I became intensely interested in its utilitarian form, its mysterious function, its gradual decay, and its contrasting relationship with the woods which surrounded it. From the walled platform at the top – maybe only 4 metres high – all that was visible was the surrounding forest. I liked the fact that it was now devoid of function; I could view it simply as an object in the trees, removed and detached, yet simultaneously part of the landscape, and part of me. It started something – a slow train of speculative thought – which has continued unabated.

I now feel less clear about what “landscape” actually is, and about what we mean by “nature” and “manmade”, than I ever have. The sense of precision in the work is deceptive, and shifting.

The technique you use involves a complex layering of sharp lines and flat colour so that the paintings resemble a curious mix between architectural blueprint and photographic negative. Do you spend a lot of time drawing and does photography have an important role in producing your work?

The starting point for all my work is an encounter with a place. Sometimes this is intentional (when I travel to experience a specific location) and sometimes accidental (those miraculous chance stumblings). My main method of recording initial responses and ideas is in fact writing. I always have a black A5 notebook with me at all times, which is a messy mixture of note-making and very quick drawings. I also take photographs, which often become a source for the paintings.

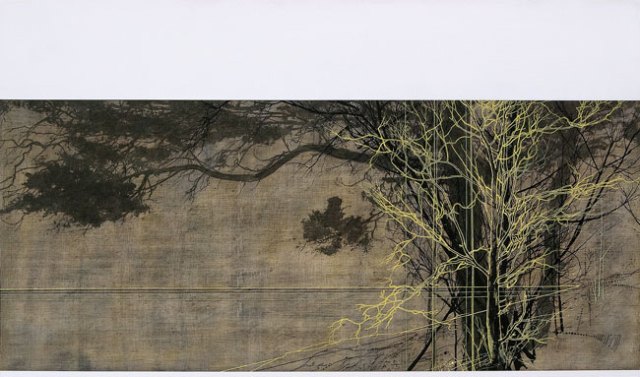

The preparatory drawing happens within the paintings. I first create a layered surface to work on, then draw directly onto this with oil paint, leaving the layered overlapping drawings deliberately and subtly visible in the finished piece. I want people to see the process of arrival.

There is an internal border in your paintings as they are banded top and bottom with wide white lines. What is the purpose of this composition?

This stems from previous abstract work which, although always based on landscape, veered towards minimalism. Often in this older work, the reference to “landscape” was the presence of horizontal lines and bands of grey and white. Gradually (over years) the figurative elements began to emerge more clearly. Now I enjoy making work which hovers on the edge between space and surface. I create an illusion of depth, but counter this illusion by reminding the viewer of the objective reality of the painting. The white bands at the top and bottom are part of this process.

You work with a very reductive palette which combines with the simplification of form to present an almost abstracted vision of the landscape, despite the precision of the drawing. The impact of a painting like Reservoir 2, Cadmium Red is initially one of pattern, colour and line, with an understanding of the actual subject matter emerging only after some consideration. This means the work bears a lot of examination. What is the importance of colour to you and what governs your choice of palette?

Colour is obviously very important in my current work. Previously, I spent a long time using only reduced colour – greys, black, white, ochre. I felt (along with other artists working in the 90’s, and looking back to artists like Robert Ryman) that colour should not be an issue. Contrary to this however, I occasionally punctuated these neutral tones and surfaces with brilliant flashes of pure flat colour, creating a “vibration” derived from observations of the urban environment.

This abstract sense of colour and surface contrast is brought into the new work. In many ways, although I am painting some recognizable landscape forms, such as trees, I see the work as abstract – a series of interweaving patterns, lines of different weights and rhythms, dots, negative spaces, balance between subject and ground.

For example, many things in Reservoir 2, Cadmium Red (below) do not make sense in terms of illusionistic space. The overlapping of the pier structure and the red trees defies conventional reading. I like the idea that they bear up to scrutiny. They are the result of long periods of careful consideration.

The way the colours work in layers confuses the space and perspective in the paintings by aligning something that could be in the foreground with something else that should perhaps be in the background. The fact they share the same flat tone brings them together and helps create an overall absence of actuality in the perspective. Is this a conscious decision to again reduce the landscape and allow you to focus on layering what effectively become motifs – trees, bridges, paths etc – rather than recording a real scene exactly as it is?

I’m not interested in depicting landscape as it really is because I don’t think that “real” is a simple idea, either in painting or in reality. I’m fascinated by the fact that landscape is an invented tradition. Many of our ideas now about what landscape actually is stem from a construct which finds its source in Art – writing, painting, poetry. The idea of “landscape” is real in the sense that it exists in our minds, but when you walk in the mountains what you see, think and feel, may be formed by so many previous histories. So, for example, even the desire to walk in the mountains in the first place (for whatever reason) is a result of influence; whether from Japanese wandering poets, climbers, explorers, artists, naturalists or bird-watchers.

None of this detracts from the pleasure of the walk; in fact it enriches it enormously. I am excited by the notion that everything we see is to some extent pre-conditioned, because getting beyond that – creating your own language – becomes a challenge.

The absence of actuality (in this sense) perhaps also relates back to the history of landscape painting, where artists like Claude could create a convincing idealized illusion of fake reality, which eventually through the grand tour, became the temporary blueprint for perceived notions of “actual” landscape.

The popular idea of what constitutes a landscape can be seen in the fixed idea of celebrity-endorsed viewpoints, such as Scott’s View or Queens View, which come with their own laybys, signposts, text panels and map symbols. Tourists disembark to capture the landscape.

I am trying to bring together these histories of perception with modernism’s focus on the object, involving multifarious viewpoints.

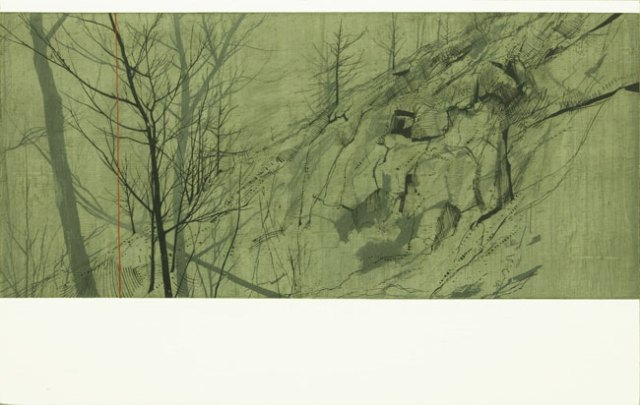

The Quarry Edge paintings differ. They seem to be presented in a more naturalistic style and retain a realistic landscape dimension, albeit one still line based and tonally reduced. Is this naturalism a direction you will be developing more in the future?

The Quarry Edge pieces are trying to set up a contradiction between the naturalism of their depiction with the hovering multi-layer presence of an abstracted diagrammatic reduced building.

I am very interested in (mostly disused) quarries for several reasons. They are artificially created cliff landscapes, reminiscent to me of early formative landscape studies by Durer, Breugel or Leonardo. They are also absences, or voids, in a hillside. Their purpose is to provide building materials for the constructed world. The quarry in these paintings is gradually returning to a natural state, although the impulse of humans to build, find shelter and travel is also part of an entirely natural process. The Larch trees along the top edge of this quarry are clearly part of a plantation. The initial response to these works may be that they are wild or natural, but the real issue is far more complex.

Your style translates very well to printmaking and you have produced a series of lithographs. Is this something you would like to do more of and would you look to explore any other techniques, for example screenprinting or woodblock?

Yes, definitely. I loved the experience of working at the Printmakers Workshop in Edinburgh. I’d really like to do it again, and experiment.

You are involved in a forthcoming exhibition to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Edinburgh College of Art. How do you view the current state of art education?

I have not visited Edinburgh Art College for a while, but from what I can gather it seems to be moving away from the traditional grounding in compulsory figure drawing. I can see the wisdom in teaching students to think for themselves, to avoid spoon-feeding, but this needs to be in dialogue with practicing professional Artists. I also feel that a real grounding in the discipline of drawing can set up a student to understand themselves, and provide them with the tools to express their ideas, whether in installation, painting or sculpture.

I was talking to a London-based gallery owner the other day who was very worried about the lack of good painting coming out of Art Colleges in London. I am personally alarmed at the rate at which courses in the arts are being dropped, for example, at Strathclyde University, or the tragically cancelled weaving course at Duncan of Jordanstone in Dundee. Funding is tight, and priorities are clearly shifting. I worry for the future of the arts in Scotland.

You have done many educational art workshops, including at the National Galleries of Scotland and others involving studying the environment. Do you feel this experience, working through ideas, experimenting with techniques and theories, can bring anything to your own art practice?

Absolutely. I have gained immeasurably from this experience, and would encourage anyone involved in their own practice to get involved. Gallery education can contribute enormously to your understanding of things, whether working with children or adults, art from the past or contemporary work. It stretches you and forces you to think on your feet. It is also one way of being paid properly for your skills.

How did your forthcoming exhibition with Graeme Todd at Czytelnia Sztuki in the polish city of Gliwice come about? The Soviet era architecture of Eastern Europe would work well with your style, have you visited Poland to produce new work?

This was through a Polish Curator and Art Educator called Ola Wojtkiewicz, who knew us both. I am looking forward to it, as I love Graeme’s work.

What other plans do you have for the future?

My main objective at the moment is to build on the show I have at Sarah Myerscough in London. That was the end result of 7 months work, and I am keen to develop new work now. I want to continue to establish more of an international career, and to show my work in a larger public space in Scotland.

Muliti-award winning artist Andrew Mackenzie was born in Banff in 1969 and now lives and works in the Scottish Borders. He is currently exhibiting at Sarah Myerscough Fine Art in London (until 31st July). A PDF brochure of the show can be viewed here.

I have followed Andrew’s career since he was at art school. It has been fascinating and I love the connection between writing and art. The quarry paintings intrigue and unsettle me – not a bad thing!