Andrew McCallum Crawford: Arthur’s Seat

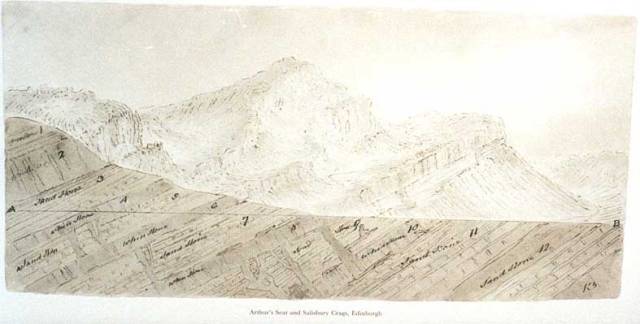

A replica of a watercolor print by geologist James Hutton: ‘Arthur’s Seat and Salisbury Cross, Edinburgh’

The grass is full of mud. I feel responsible. It was my idea to meet. I know what lengths she has gone to. It can’t have been easy for her.

Arthur’s Seat is directly ahead. The summit is shrouded in mist. The summit is up in the clouds. It was my idea to meet her in Edinburgh, but the suggestion to climb to the top of an extinct volcano was hers. I tried not to read too much into it. I’m still trying. There was a storm last night. Flights were cancelled. I was worried she wouldn’t make it, but she is here.

I want to hear her voice. Her accent is different to what it was. A southern English vowel jars now and again, but it is still her voice. I want to sit down with her, I want to look into her eyes and tell her things. I want to tell her why we are here, but it is hard to find an opening. She talks, and I make silent excuses to myself. I am worried about being clumsy, of saying something she won’t like.

We only have so much time, and it is running out.

The satchel on her back looks heavy. She turns to me. ‘Could you carry this?’ she says.

‘Probably not,’ I say. I am joking, but she does not look pleased. ‘Come on,’ I say, and manage to slide one of the straps down her arm.

‘No, it’s okay,’ she says.

I move behind her and remove the other strap, but she is resisting. I laugh, and pull harder. I think I hear her laugh, too. I think I hear her say my name. It is the first time she has used it since we met. But I can’t be sure. I want her to say it again. I want her to look at me and acknowledge to my face that she knows she is here with me.

We walk slowly round the bottom of the hill. She tells me things about her life, about things that have happened to her. She says something about music. Pianos. We both play. Then something about a man she knows. ‘He couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket,’ she says. ‘Have you ever heard that?’

I don’t know who she is talking about, my head is somewhere else, but I like the expression.

The ascent – the real ascent – begins. She is a fit woman. She strides into the distance, high and far, almost disappearing into the mist. It is impossible for me to keep up.

‘Come on, old man,’ she laughs. ‘It’s not that steep.’

But it is. It is too steep for me. I have to take it slowly. Time is running out, but I can’t go any faster. Then the rocks begin. The mist catches in my throat. I see wet steps fashioned out of boulders.

She has stopped. She has to be careful. Her boots have no tread, she says.

I take the lead. I have to prove something.

I offer her my hand.

She looks at it and I know she is scared to touch me.

She is looking at my hand as if taking it would be going too far.

She grabs my sleeve. I feel the tug through the material. I want to touch her hand. I want to feel the skin of her hand in my hand. I want this woman, who was once my lover, to touch me. I want her to want to touch me. I want confirmation that I am still a man in her eyes, that I am still in the game. Back then, our relationship was defined by the word ‘control’. I couldn’t control her. I still can’t. I want something she won’t give, something she can’t give.

She lets go.

We are almost there. I step onto the final boulder and I hear her slip. I turn, her right hand skids off a rock and she falls awkwardly on one knee.

‘Jill!’ I reach for her and again she takes my sleeve. It is my fault for not insisting. ‘Give me your hand,’ I say.

But she doesn’t. She can’t. She has tissues in her satchel. She cleans her hand and scrubs the stain on her jeans. Thank God she’s all right.

‘It’s a good job I’ve got a pair of trousers with me,’ she says.

I don’t believe her. ‘What?’ I say.

‘I told everyone I was coming here on business,’ she says. ‘I wore trousers on the flight. I got changed when I arrived.’

I don’t want the details. I don’t want to hear this.

We walk slowly to the cairn. Her phone rings.

‘Can I get this?’ she says.

The phone is in her hand. What am I supposed to say?

‘Hi, Paul,’ she says, and I am consumed by something I haven’t felt in years. ‘Oh…uhuh, yeah…look, Paul, I’m just – what am I doing? I’m just going into a meeting. I’ll see you tonight, okay? Bye.’

She is an excellent liar. There could never be a future in this. But this is not about the future. It never has been. It is about the past, and the things I have to tell her about it.

We have reached the summit, but there is no view of the city. There is no view of anything. All I can see is her, standing in front of me. She is veiled in mist, like an apparition. I imagine that the mist has turned to smoke. Smoke is weeping from the dead rocks. Something has been rekindled and is awakening, coming back to life.

‘I got this for you,’ I say, and give her the envelope I prepared this morning. She opens it. ‘It’s a lucky charm,’ I say. ‘To ward off the evil eye. Do you know what the Greeks say about the evil eye? It’s not as bad as it sounds. If you look at someone and you think they’re beautiful, you can put the evil eye on them. You’re beautiful. I’ve told you that before. It’ll protect you.’

She examines the gift closely, as if it might decipher what I just said.

‘I should have given it to you earlier,’ I say. ‘You might not have…I’ve been falling in love with you for the last three months.’ The words are out, where they have to be. It is too late to take them back. Time is up. ‘I know it sounds…but I can’t think of any other way to describe it. I’ve fallen in love with that girl again, the one I used to know. I wish we hadn’t lost touch. I know you’ve forgotten what…’

‘Stop, please,’ she says. The trinket hangs limp like something useless, like something lifeless, like mist, like something only a fool could believe in. ‘Please don’t say that.’

‘But there’s so much…’

She clenches her fist and the chain snaps. The stones scatter on the ground.

A dozen blue eyes stare up at us from the muck.

I hear something in my throat.

‘I’m sorry,’ she says.

She doesn’t move. I gather the stones myself. I can’t bear to look at her. ‘Why did you come?’ I say. ‘What’s the point of you being here?’

‘You’re right,’ she says. ‘This is all a mistake. It should never have happened.’

I put the stones in my pocket. She can do what she likes with the chain. ‘All I wanted was to talk to you,’ I say. ‘Is that what you’re afraid of?’

‘Don’t speak to me like this,’ she says.

The mist is getting thicker. It confines us. It is inside us, making it hard to breathe. Our voices. We sound like people who are drowning.

‘Why did you come?’ I say.

She struggles to find the words. The chain is tangled round her fingers. ‘I’m not as stupid as you think,’ she says.

I know she isn’t stupid. I think of the lies she has told. They have a life of their own.

Her hand is outstretched. The skin is grazed. I see blood. Blood and what remains of my gift. The silver has lost its sheen. Parts of it are red. ‘You’d better keep this,’ she says.

‘I got it for you,’ I say.

‘Okay,’ she says. ‘Give me the stones.’ I watch as she tries to put the charm together again, but it is impossible. She opens the envelope and places the pieces carefully inside.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I say, even though it does. I am desperate, tired of being alone. ‘I apologise. It’s all my fault.’

‘You look as if you hate me,’ she says.

‘I don’t hate you,’ I say. I could never hate her. Not the way she means.

We find the way back to the steps. She offers me her hand. I hold her gently – I do not want to hurt her any more than I have. Hurting her was never my intention. We are up in the clouds. Her face is close. I watch her breath dance with mine. We stand here, looking at each other. I am trying to read her eyes, to read her expression, but I don’t understand. I don’t understand her. I don’t understand any of this.

Andrew McCallum Crawford’s short stories have appeared in many magazines, including Interlitq, Gutter, Northwords Now and Body. His latest collection, ‘A Man’s Hands’, has just been released. He lives in Greece.

Comments

3 Responses to “Andrew McCallum Crawford: Arthur’s Seat”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...[…] Fiction in New Linear Perspectives Fiction at McStorytellers Fiction at The Ofi […]

[…] Another story in B O D Y One more story in B O D Y Fiction in New Linear Perspectives Fiction at McStorytellers Fiction at The Ofi […]

[…] A story in B O D Y Another story in B O D Y One more story in B O D Y Fiction in New Linear Perspectives Fiction at McStorytellers Fiction at The Ofi […]